“I die in the Catholic, apostolic and Roman religion in which I was born over 50 years ago”: the prelude to the will produced by Emperor Napoleon segregated on the island of Saint Helena is only the apogee to the sacred journey concluded by the corsican leader on the globe. The eagerness to honour the Catholic liturgy was satisfied by Abbot Antonio Buonavita who arrived at Longwood House (1819) to recite the Sunday Mass, by the extreme anointing administered by Abbot Ange Paul Vignali and by the planning clarified to officiate the funeral.

The tendency has been combined with the metamorphosis experienced by the agnostic seduced by Pascal’s bet: the weak exegesis has been denied by the climate of religious rebirth induced by the apologetic work “Génie du Christianisme, ou beautés de la religione chretiénne” written from 1795 to 1799 by Viscount François-René de Chateaubriand (Saint-Malo, 4 September 1768 – Paris, 4 July 1848) and from the ethical order risen from the 1930s and 1940s to the 19th century. Robert Augustin Antoine de Beauterne (1803 – 1846) wrote several papers to disqualify the doubt about the solid religiosity of Napoleon exhibited by the French entourage transferred to the Atlantic island. The line defended by the author was promoted by the memoirs produced by General Carlo Tristano Montholon, Secretary Louis Marchand, by the doctor Francesco Carlo Antommarchi and antithetical to the skepticism expressed by Count Emmanuel de Las Cases and also by General Gaspard Gourgaud.

“The most noble footprint of the deity – declared Beauterne – is written and reflected in this individual who had the mission of protecting and realizing the purposes of paradise on the world. It was Providence that drew upon him every gaze and paved the way for his unprecedented elevation, the healing of spirits, the reform of customs, the regenerated society. The criticism of honesty about the emperor’s religious faith is more false than real, more ideal than positive. Napoleon humbled himself and reconciled himself to God, he annihilated himself in the divine presence as much as he stood before men. This great man died a penitent in the arms of religion”.

The will also preserves the political legacy handed down to the world ignorant of the colossal tragedy suffered by the man imprisoned and oppressed by the most powerful states affiliated to the anti napoleonic alliance.

“I connect the reproach and shame of my death to the royal family of England”: the Emperor of the French, depleted by the liver disease exacerbated by the tropical climate on the island of Saint Helena and skimmed by death, crossed on the field of 60 battles, dictated the epilogue of 60 thousand diplomatic letters to save also the immortality undermined even on the table for the autopsy demanded by the Corsican General.

“If I lose consciousness, you still don’t have to allow the English doctor access. You will remain true to my memory and do nothing to offend her. I have laid at the base of all my laws and actions the strictest principles. Unfortunately the circumstances were serious: I could not let the indulgence prevail and I had to procrastinate many good things. Then the showers came. I could not let go of the bow and, so, France remained without the liberal institutions that I had intended. But she judges me with indulgence and evaluates intentions, she loves my name and my victories: imitate her! Be faithful to the opinions already defended, to the glory already won: beyond this there is nothing but shame and confusion”.

May 5, 1821, 5.49 pm: the tropical sun fell on the sea and Napoleon’s heart is silent. The embalmed body covered by the blue cloak worn at Marengo lay on Austerlitz’s field table.

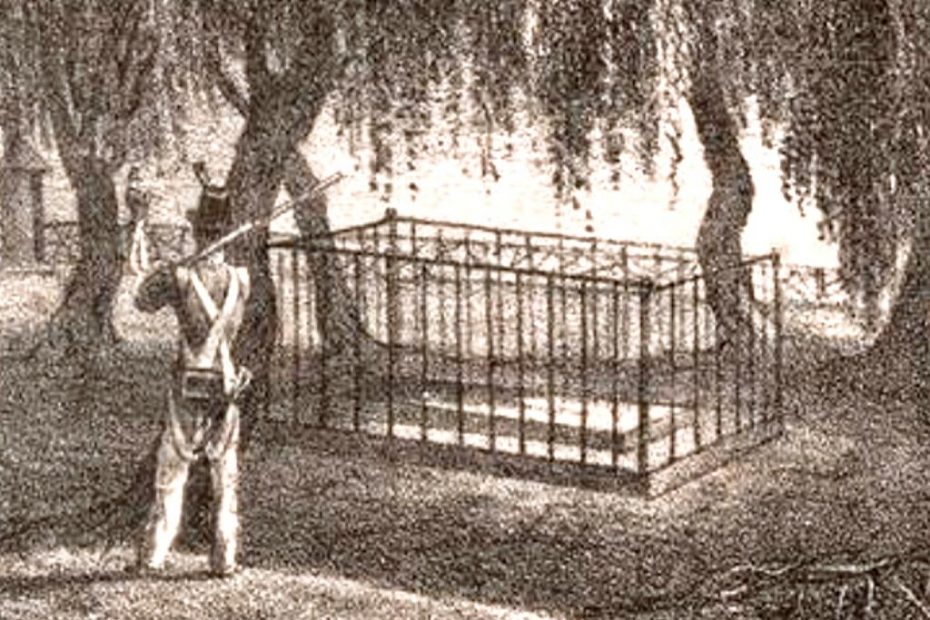

Sir Hudson Lowe alias the English governor in Saint Helena denied transferring the imperial body to the Old Continent and the inscription Napoleon on the tombstone to curb the expansion to the known myth of Alexander, Caesar, Frederick. The tomb remained, then, anonymous but the saga also grew on Lowe’s Memorial (1830).

“When I was informed by an artist on the island who was delegated by the French to create the silver plate for Napoleon’s coffin, I declared to Count Montholon that it could not be placed with the epitaph: the prohibition had been established by the English monarchy. The obstinacy, ridiculous and petty, ignored the ubiquity of Napoleon’s epigraph: to obliterate the prodigious power of a man who had left traces of it from the Pyramids, the Kremlin would have had to tear the pages of history, eliminate the memories of a hundred million men, knock down statues and arches of triumph”.